The I2G indictment took place in 2017. The indictment included the initials of eight alleged “victim investors” along with their gross purchase amounts, which were implied to be losses. We pointed out that the government possessed data indicating that the three key purchasers referenced in the indictment were not victims; rather, they were successful promoters who earned significant commissions through i2g. Three of the “non-witnesses”—Michelle Kim, Sheon Jeong, and Queyenne Pepito—collectively earned $870,000 in commissions. Those documents have been uploaded. Hundreds of transactions document the internal transfer of tens of thousands of dollars from other distributors to Jeong, Pepito, and Kim, per US 7240.

In 2019, the government superseded the indictment, including a count of conspiracy to commit securities fraud. Attorney Kenyon Meyer, partner at Dinsmore and Schol Louisville office, filed to dismiss the indictment for failure to name an overt act. Judge McKinley denied the motion based on the assumption that the government would present specific overt acts as misrepresentations that directly resulted in the purchases by the alleged victims. This never occurred, though.

An overt act by a co-conspirator that resulted in the alleged securities purchase needed to have occurred after November 2014 for the superseding indictment to be valid under the statute of limitations. All purchases listed in the initial indictment fell outside this time frame. The Emperor program concluded in July 2014, meaning there could not have been any additional Emperor purchases that would qualify within the statute of limitations. To address this requirement, the government claimed that Maike made a side deal with a non-conspirator, Scott Majors, which led to payments that could qualify as a purchase occurring after November 2014.

In reality, no purchase occurred within the statute of limitations. A sale to S.H., also known as Syed Hussain, a non-U.S. citizen, took place in London in August 2014, which was outside the statute of limitations. Majors used “lent funds” from Maike to create “gift certificates” to fulfill three emperor package purchases in the same way as cash payments. Hussain’s enrollment date was in August 2014.

The government argued that subsequent bank wires related to Hussain’s initial purchase in August 2014 made it eligible for the statute requirement. In October of 2014, SH wired Major as repayment for the August purchase. The October repayment to Majors, a non-conspirator, precluded the requirement of an overt act by a conspirator and remained outside the statute of limitations.

The government’s argument expanded the notion of an “overt act” by claiming that Major’s repayment to Maike in November 2014, which occurred after Hussain’s repayment to Majors in October 2014 for the original purchase made in August 2014, was the overt act within the statute of limitations. However, it is clear that merely receiving money does not qualify as an overt act and could not have been the action that led to Hussain’s initial purchase. Additionally, since Majors was neither an alleged victim nor a conspirator, the possibility of an overt act by a co-conspirator leading to Hussain’s August purchase was effectively ruled out.

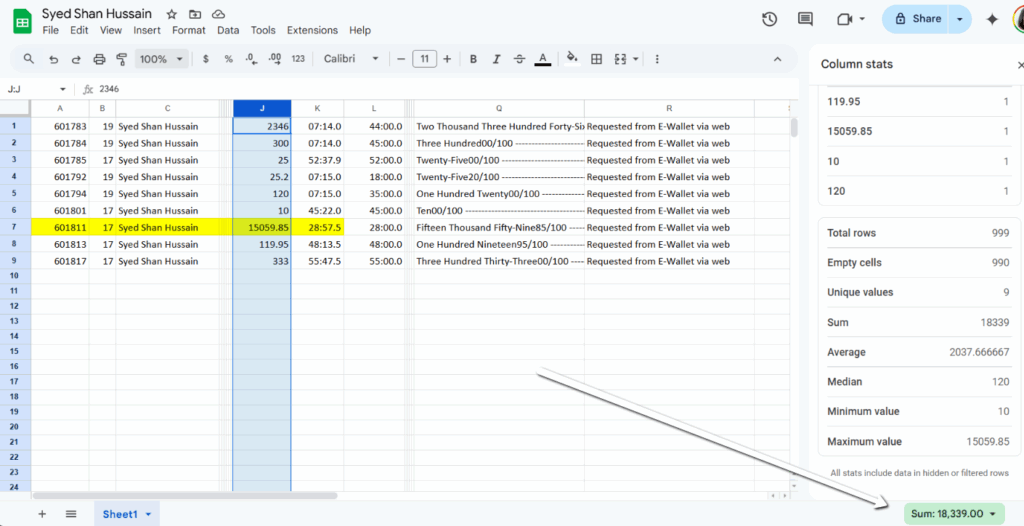

Like most of the alleged victims, SH did not testify. Since the commission data related to all purchasers was filtered out of their data representations in 101i, SH’s status as a victim investor is based on hearsay. Data from US 7240 indicates that Hussain withdrew over $18,000. Additionally, the fact that his purchase occurred outside the United States suggests that U.S. securities law may not apply.

Despite this reasoning, the Court sided with the prosecution. The judge noted that if he were mistaken, the appellate court in Cincinnati would likely overturn the conviction if it were to occur.

I have attached the commission records for Syed Shan Hussain, which show nine withdrawals totaling $18,339.00. This situation illustrates a case where a non-witness is introduced through hearsay as a “victim investor” who made a “securities purchase.” Similar to the non-witnesses Kim, Pepito, and Jeong, Hussain was labeled a “victim investor” without any supporting commission records to prove that he was indeed an actual victim. The term “victim” implies financial losses; however, since the “victim list” was compiled solely based on gross purchases without considering earned commissions, the jury was misled into believing that losses had occurred.

Cross-examining individuals alleged to be “victim investors” was crucial to determining whether their earned commissions and personal promotions would disqualify them from being classified as “victim investors.” Since Syed’s case played a significant role in assessing whether an overt act connected to a victim investor fell within the statute of limitations, it is clear that these misleading labels on jury instructions hindered the fairness of the trial. Furthermore, the fact that Syed was not a U.S. citizen, was relevant to evaluating compliance with U.S. securities laws.

It cannot be denied that the act leading to Hussain’s purchase in August occurred between a non-conspirator and Hussain, which precluded the required overt act by a conspirator and was outside the statute of limitations.

The Sixth Amendment’s Confrontation Clause guarantees criminal defendants the right to confront witnesses against them, which includes the right to cross-examine those witnesses. This right is crucial for ensuring the accuracy of the truth-determining process in a trial, allowing the defense to test the credibility and reliability of the prosecution’s witnesses.

The reason why the Constitution has provided a confrontation right for all defendants to confront their accusers is apparent. Without such protections, the government has offered unverified hearsay as factual evidence of “victim investors” who are not victim investors per their own data to convict defendants, as occurred in the i2G case unfairly.