The I2G case revolved around Kansas lands that Rick Maike purchased using three million dollars in cash proceeds or profits from Infinity Two Global. On January 14th, 2015, an affidavit was filed to seize the Kansas land. Only after 18 months of Maike’s refusal to settle regarding the lands did the government push the envelope with a criminal indictment.

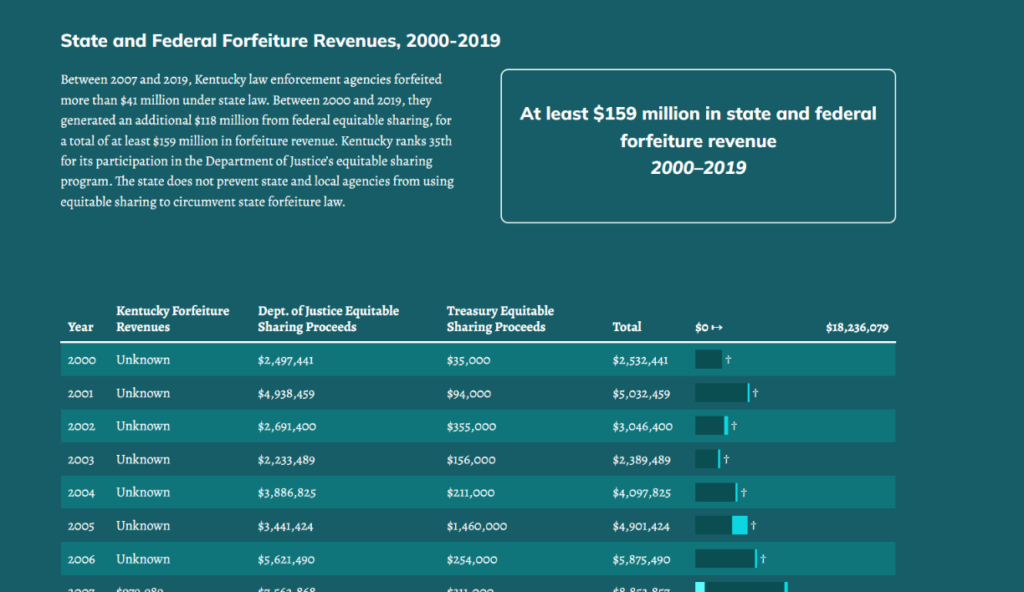

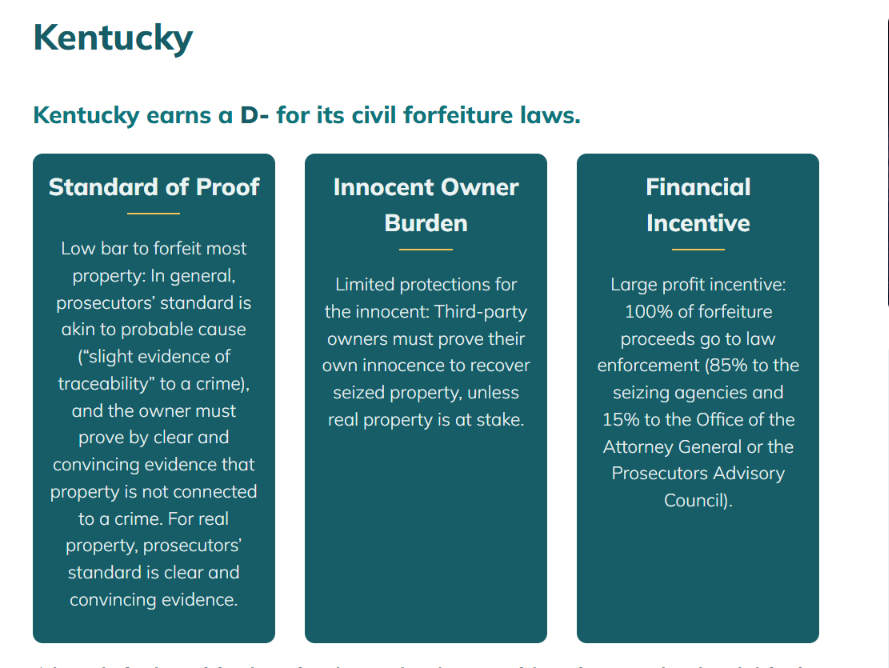

In Kentucky, the standard for acquiring someone’s land or property is very low; it only requires a minimal amount of information and does not necessitate a criminal conviction. A mere claim of suspected wrongful activity is sufficient to seize someone’s property. Between 2007 and 2019, Kentucky law enforcement agencies forfeited more than $41 million under state law. Between 2000 and 2019, they generated an additional $118 million from federal equitable sharing, for a total of at least $159 million in forfeiture revenue. Kentucky ranks 35th for its participation in the Department of Justice’s equitable sharing program. The state does not prevent state and local agencies from using equitable sharing to circumvent state forfeiture law.

In this case, Agent McClelland misrepresented Infinity Two Global as an investment opportunity instead of a multi-level marketing company. The affidavit for the lis pendens (which is necessary to acquire the land) does not mention that the company operated as a multi-level marketing organization or that the “proceeds” referred to “commissions” earned from product purchases or related to the “usage” of the products. It also failed to mention the diverse range of products available at that time, including social games, fantasy sports, and travel. Furthermore, it did not address the fact that $38 million was paid in commissions, which constituted the primary source of the alleged victim investors’ “purchases.”

The dispute over the land and the inability to reach a civil settlement escalated the situation, resulting in a criminal indictment that implicated top distributors. Maike was unwilling to give up the land. Even the i2G Court questioned whether this case could have been solved civilly.

It is important to note that a vicious campaign was underway to destroy the company. FBI Agent McClelland was working directly with a saboteur named Chuck King, who declared war on the company after Maike questioned his I2G mailing system. Distributors had invested over $25,000, and a mailing had not taken place at that time.

On May 9, 2014, Maike held a conference call with the distributors, during which he instructed them to file small claims lawsuits against Chuck King, who was also on the call. The following day, on May 10, 2014, Chuck King attacked the company, declaring that he “had nothing to lose,” while I2G did. He vowed to send Maike and the top distributors who participated in the call, including Hosseinipour, to prison as an act of revenge.

The campaign that followed was both vicious and relentless. It involved a full website with form letters to be sent to the Attorney General, the FBI, and various state agencies, as well as dozens of emails, videos, calls, and messages aimed at discrediting the company. Chuck King’s correspondence with FBI Agent McClelland heavily influenced the investigation that followed, a fact that King did not deny. In fact, he bragged in several videos that his actions played a key role in leading to the investigation and subsequent indictments.

King pointed fingers at Hosseinipour, Anzalone, and their spouses, alleging they worked directly with Maike and Barnes in a separate company, Bidxcel, which had closed voluntarily, claiming they conspired from the start. However, there was no evidence that Hosseinipour met Maike or Barnes before her involvement as a distributor in I2G.

Despite this, McClelland presented this tale to the Grand Jury, suggesting that all parties had worked together previously. When the jurors asked how he knew the promoters did not believe in the company and what they had been told, McClelland misled them into thinking there had been a conspiracy originating in BidXcel. During the I2G trial, he admitted that he did not know if this assertion was true; he had only relayed what Chuck King had told him.

During the trial, the government put considerable effort into undermining the character of the defendants regarding their alleged roles as distributors for Bidxcel. Anzalone stated that he believed everyone met at Bidxcel; however, he claimed that Hosseinipour did not work with Maike or Barnes because they were in separate groups. However, Hosseinipour never met Maike or Barnes at that time. The government presented no evidence to suggest that she had any prior contact with Maike before being recruited by Anzalone into I2G. Anzalone acknowledged Hosseinipour went to work for a different company after Bidxcel and did not know about the formation of I2G Infinity Two Global.

It is important to note that the i2G Infinity Global trial occurred nine years after the launch of I2G. Many individuals had poor memories regarding the events. Richard had undergone serious brain surgery, which impacted his recall. The government and FBI sent Hosseinipour’s hangout videos to distributor witnesses, attempting to prompt witnesses to say they had seen the videos before they signed up. However, all witnesses testified that they joined based on the influence of their sponsors, none of whom were Hosseinipour. Furthermore, not a single witness testified that they remembered ever speaking with Hosseinipour. No witness stated that Hosseinipour misrepresented the business or that she influenced their purchase over their personal sponsors.

McClelland testified that his investigation began in June 2014, shortly after King started his campaign and began interacting with Agent McClelland. Less than seven months later, on January 14, 2015, McClelland filed an affidavit to seize the Kansas assets, which is included in the attached documents. The original affidavit does not state that Infinity Two Global is a multi-level marketing company, nor does it mention that the investments were “product purchases” with resale rights, or that $38 million in commissions were paid to distributors.

Based on the six months of ongoing negotiations surrounding the land, it is doubtful whether this case would have ever proceeded to a criminal indictment had Maike given up his land.